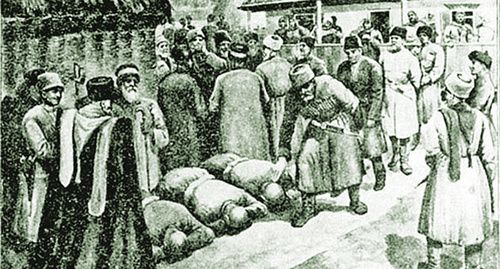

Blood feud – how they kill now in the Caucasus

The blood feud is a custom that had formed during the clannish social system as a universal means of defending the honour, dignity and property of the clan. It implies the duty of casualty's relatives to take revenge on the killer or his relatives 1. In recent months, several reasons have appeared to make sure – in Northern Caucasus, the blood feud is by no means a part of history; it continues acting as an actual social mechanism.

Yamadaevs – Kadyrov's feudists

On January 30, 2017, the "Novaya Gazeta" published an article, telling with reference to law enforcers that the assassination attempt on the Chechen leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, which had been plotted in spring of 2016, but was prevented, could be backed by Yamadaev brothers 2, feudists to the head of Chechnya.

In March 2017, the Chief Investigating Department for Chechnya of the Investigating Committee of the Russian Federation (ICRF) issued a resolution to search Isa Yamadaev as a suspect of the attempt on Ramzan Kadyrov 3. The resolution stated that "since May 2016, Yamadaev, I. B., assuming that the head of the Chechen Republic, Kadyrov, R. A., was guilty of the death of his brother – Yamadaev, Kh. B., acting out of the feeling of blood feud, decided to kill Kadyrov." 4

Reports that the Yamadaev clan had declared blood feud to the clan of Kadyrov clan appeared earlier. Thus, after the murder of Ruslan Yamadaev in September 2008, the Reuters reported that his brother, Sulim Yamadaev, allegedly declared blood feud to Ramzan Kadyrov. Then, Sulim himself refuted this information 5. In March 2009, in Dubai, an attempt was made against Sulim Yamadaev himself, who died as a result thereof. Isa Yamadaev, who, after the deaths of his brothers Ruslan and Sulim, headed the family clan, could hardly escape an assassination attempt on him in summer of 2009.

In 2010, at the commemoration of Sulim Yamadaev in Gudermes, Ramzan Kadyrov and his cousin Adam Delimkhanov were present, which gave experts the ground to talk about an amicable agreement of the two clans in conflict.

In 2010, at the commemoration of Sulim Yamadaev in Gudermes, Ramzan Kadyrov and his cousin Adam Delimkhanov were present, which gave experts the ground to talk about an amicable agreement of the two clans in conflict.

According to the Sharia, a reconciliation of feudists allows terminating criminal prosecution. When Isa Yamadaev sent a letter to the court of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that he had lifted all the claims against all those accused of the attack on his brother, the Dubai Court of Appeal replaced the life sentence earlier passed to the Iranian Makhdi Lorniya and Maksudjon Ismatov, a Tajik citizen, the figurants in the Sulim Yamadaev's murder case, for 27 months in prison each.

However, according to the "Novaya Gazeta", the above reconciliation was artificial and virtually not recognized by either party. Allegedly, it was necessary just to remove charges of organizing Sulim Yamadaev's murder from Adam Delimkhanov.

According to the newspaper, the two surviving Yamadaev brothers – Badrudi and Isa – still "regard Ramzan Kadyrov guilty of the murders of Ruslan Yamadaev, the State Duma MP from Chechnya, and Sulim Yamadaev, the commander of the "Vostok" (East) battalion," and it is with the Yamadaev name that the recent attempt on Ramzan Kadyrov is associated by Chechen law enforcers, who are conducting the investigation.

According to the newspaper, the two surviving Yamadaev brothers – Badrudi and Isa – still "regard Ramzan Kadyrov guilty of the murders of Ruslan Yamadaev, the State Duma MP from Chechnya, and Sulim Yamadaev, the commander of the "Vostok" (East) battalion," and it is with the Yamadaev name that the recent attempt on Ramzan Kadyrov is associated by Chechen law enforcers, who are conducting the investigation.

On December 21, 2017, law enforcers conducted an operation in Gudermes aiming to find Isa Yamadaev and his younger brother Badrudi; about a hundred special agents arrived in the village to search for the brothers. The police explained such an agiotage by the fact that Isa Yamadaev had been put on the federal wanted list on suspicion of an assassination attempt on Ramzan Kadyrov. Although in the context of the background of Kadyrov-Yamadaev clannish relationships, the situation looks like the use of administrative resources for blood feud.

Blood feud to militants' relatives

Another story on blood feud declaration in Chechnya has to do with the aggravation of the situation in the republic after the armed clash in Grozny on December 17-18, 2016. According to the official version, supporters of the "Islamic State" (IS), banned in Russia, waged an attack on Chechen law enforcers. After the clash, Chechen authorities organized several rallies, where residents of towns and villages demanded not only to evict attackers' relatives, but also to declare blood feud to them. Such rallies were held in the village of Prigorodnoe, in Grozny, Tsotsi-Yurt, Kurchaloi and Shali.

For example, the rally in Prigorodnoe was attended not only by ordinary villagers, but also of officials – an assistant to the head of Chechnya and officers from the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), as well as clergymen from the Spiritual Administration of Muslims (SAM) of Chechnya. The participants of the rally demanded to evict relatives of Zelimkhan Bakharchiev, suspected by the police of organizing the December attacks, out of Chechnya. In a conversation with the "Caucasian Knot" correspondent, the SAM representative reported that "at the rally, relatives of the policemen killed by the bandits declared blood feud to this family."

The "Caucasian Knot" correspondent reported that at the rally held on December 30, 2016, in Grozny with the participation of relatives of killed policemen and militants, as well as members of their clans, elders and theologians, Adam Shakhidov, an adviser to the head of Chechnya, called to forgive relatives of the militants killed during the special operation and give up the blood feud. However, relatives of the killed policemen refused to take such a step.

A source of the "Caucasian Knot" from the Chechen Ministry of Public Health also reported that the three supposed militants, detained after the December clash in Grozny, who were wounded and hospitalized, were taken out of there by armed people and killed. On this occasion, Oleg Kashin, a columnist of the "Deutsche Welle", reported, referring to his anonymous sources, that the wounded militants were killed by their own relatives, who has faced a choice "either you kill them yourselves, or we liquidate all your families, including small children." 6 So far, this information remains unconfirmed, but it is known that at least one alleged member of the militant grouping, Madina Shakhbieva, who was wounded during the special operation in Grozny, was taken out of the hospital, killed and buried without funeral rites. This information was confirmed by a reliable source of the Human Rights Centre (HRC) "Memorial", who also said that Shakhbieva's relatives, including law enforcers among them, "refused" from her after she was abducted from the hospital.

The expulsion of militants' relatives from Chechen villages after the 2016 clashes was not the first such episode. Two years earlier, the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, announced the introduction of the principle of collective responsibility of families for their relatives-members of the armed underground. Then, the pretext was also a militants' attack on policemen in Grozny, committed in December 2014. Thereafter, the head of the republic announced that militants' families would be immediately evicted from Chechnya without the right to return; and their houses "would be demolished together with foundations."

Igor and Alan Alborov: "numerous stab-cut wounds" for father's death

Chechnya is not the only region of the Caucasus where the blood feud tradition continues to exist. For instance, in mid-January 2016, a court in Cherkessk placed in custody Igor Alborov, a two-time European boxing champion, and his cousin Alan, on charges of blood feud-based murder.

Chechnya is not the only region of the Caucasus where the blood feud tradition continues to exist. For instance, in mid-January 2016, a court in Cherkessk placed in custody Igor Alborov, a two-time European boxing champion, and his cousin Alan, on charges of blood feud-based murder.

For ten years, the Alborovs had searched for their former neighbour Alexander Goyaev who, as they believed, had organized an attempt on Oleg Alborov, Igor's father. Having found out that Goyaev lived in the village of Udarny in the Prikubansky District of Karachay-Cherkessia, Alan and Igor Alborov came there and severely executed the 70-year-old Alexander Goyaev and his 30-year-old son Alan, by inflicting a lot of knife wounds to them.

Oleg Alborov, whose murder Igor and Alan wanted to take revenge of, was the Secretary of the Security Council of South Ossetia, and before that headed the republic's KGB. He perished on July 9, 2006, from a bomb that exploded in his car 7.

How has the blood feud custom survived till now?

Historically, for the nations of Northern Caucasus, the blood feud custom was an important regulator of social relations. Among the Vainakh nations (Chechens and Ingushes), the Dagestani nations (Avars, Laks, Nogais, Kumyks and others), the blood feud custom was regulated by a set of customary laws – Adats 8.

Historically, for the nations of Northern Caucasus, the blood feud custom was an important regulator of social relations. Among the Vainakh nations (Chechens and Ingushes), the Dagestani nations (Avars, Laks, Nogais, Kumyks and others), the blood feud custom was regulated by a set of customary laws – Adats 8.

"Among mountaineers, the blood feud is not an unrestrained, uncontrolled feeling, like vendetta among Corsicans; it is more a duty imposed by the honour, public opinion and the demand of 'blood for blood'," Naima Neflyasheva, the author of the blog "Northern Caucasus through Centuries" she runs on the "Caucasian Knot", quotes Leontie Lyulie, a researcher of the 19th century.

The blood feud had no limitation period. There were cases when revenge was carried out 50 or 100 years later, even if the perpetrator of the murder and his close relatives had died. Therefore, the Caucasian nations still believe that it is better to resolve all issues related to blood feud as soon as possible, so that the descendants could live peacefully. When a feudist dies a natural death, without getting a revenge or forgiveness, his nearest relatives – a brother, a son or a grandson – get under the blow, and if there are none of them, then, other male relatives 9.

Over time, especially with the change of social and economic conditions in Northern Caucasus, in late 19th-early 20th centuries, an understanding appeared that the blood feud, as a way to resolve conflicts, results only in an endless series of mutual murders and undermines the society from within. Therefore, with the aim of self-preservation, a number of ways to prevent murders were developed and replaced by fines.

For example, this option was adopted by almost all Dagestani Turkic nations: relatives of the killer paid a fine to the suffered party. The fine amount often depended on the influence and multiplicity of the killer's relatives 10.

A similar practice was used by other Caucasian nations, namely by Ingushes. In their turn, Chechens, for the most part, rejected reconciliation by paying the "blood price", which was considered a great disgrace by them: "We don't trade the casualty's blood," they used to say in Chechnya 11. The Terek Nogais, living in close neighbourhood with Chechens, were perhaps the only nation of Dagestan, who also refused to accept fines as compensations for murders 12.

During the epoch of the Russian Empire, and in the Soviet time, authorities tried to counter the blood feud tradition, but failed to eradicate the custom completely. For example, in the pre-revolutionary Russia, in Dagestan, an average of 600 people per year died because of the blood feud, or for other reasons rooted in the remains of the clannish system 13.

The Soviet authorities drew public to counteracting the custom of blood feud: communists and Komsomol members formed district and village committees to combat the blood feud survivals. According to judicial statistics, in 1929, 118 blood feud murders were recorded in Dagestan; in 1930 – only 30, and in 1931 – 22 murders 14.

However, even despite the cruel Soviet punitive laws (in 1931, an amendment was adopted to the USSR's Criminal Code, according to which blood feud killings were qualified as "state crimes", under Article 58, point 8, with application of the capital punishment – execution by killing 15; and later, Article 231 of the Criminal Code was adopted, which punished with up to two years in prison for refusal to reconcile 16), the authorities failed to achieve much success. In the late 1970s-early 1980s, blood feud was the main motive for 47% of bodily injuries and 70% of murders committed in large cities of Northern Caucasus 17.

Naima Neflyasheva, a Caucasus researcher, notes in her blog on the "Caucasian Knot" that it was from the second half of the 20th century that "the degradation of blood feud began – from the tradition that had its logic and self-regulation, it turned into a sort of lynching."

Today, the custom of blood feud is partly preserved in all the republics of Northern Caucasus. After the collapse of the Soviet Union – with the deterioration of the general criminal situation - the number of blood feud-based murders and injuries in the Caucasus even exceeded the pre-revolutionary level 18. Thus, in 2007, out of 170 murders, registered by the Dagestani Prosecutor's Office, 42 were assassination attempts, seven were missing persons, and four were blood feud crimes; whereas in the mid-2000s, about 15% of all murders and assassination attempts in the republic were somehow connected with blood feud 19. At the same time, as Dagestani law enforcers emphasize, it is the blood feud tradition that blocks the crime rampant in mountainous areas, where this custom is most widespread 20.

Attempts to control blood feud in Chechnya

After the advent of Djokhar Dudaev to power in Chechnya and the start of the military conflict, the situation arose in the republic that contributed to the widespread of blood feud. In the conditions when members of some clans supported the federal forces, while others were on separatists' side, hundreds of people appeared on opposite sides of the barricades; they are still accusing each other of committed crimes 21.

Attempts to somehow regulate the use of blood feud were made in 1996-1999, in the period after the First Chechen War, when the then President of Ichkeria, Aslan Maskhadov, tried to introduce the Sharia Court in Chechnya, instead of the Adat 22. This court, based on the Islamic legislation, suggested replacing the blood feud with "taleon" – "kisas" in Islam – an equal retribution 23.

This attempt was largely artificial, since the traditional image of Chechens, their customs and social relations were based more on Adats, not on Sharia canons. The influence spheres of Adat and Sharia in Chechens' social and spiritual life have always been differentiated. Sharia covered and regulated a part of family-household, religious-funerary and other social phenomena, while the Adat covered a large layer of the ethnic culture: Chechen etiquette, accentuated hospitality, respect for elders, mutual assistance, military prowess and blood feud were mostly based on the norms of Adat 24.

In 1999, when a change of central power began in Chechnya, this Adat-based code, according to Igor Kiselyov, Deputy Head of the Chief Department of the Russia's General Prosecutor's Office (GPO) for Northern Caucasus, "legally fixed the existence of blood feud tradition." 25

In September 2010, the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, created and headed the so-called Commission for National Reconciliation 26, which was called upon to resolve conflicts based on blood feud. Kadyrov called on all the feudists to forgive each other; however, he declared blood feud to Akhmed Zakaev, who was then in Great Britain and whom Kadyrov accused of involvement in the militants' armed attack committed in late August 2010 on the village of Tsentaroi, Kadyrov's clannish village 27.

According to official, not verifiable, data, during the work of the above commission, thanks to the efforts of the clergy and elders, a total of 451 Chechen families, who had been at blood feud for many decades, were reconciled.

According to official, not verifiable, data, during the work of the above commission, thanks to the efforts of the clergy and elders, a total of 451 Chechen families, who had been at blood feud for many decades, were reconciled.

On October 17, 2011, Ramzan Kadyrov abolished the Commission on National Reconciliation as having fulfilled its main mission – the settlement of blood feud-based conflicts; however, on the following day, October 18, 2011, a new commission on national reconciliation was set up – this time under the Chechen Spiritual Administration of Muslims (SAM), or Muftiate.

Not all the cases of blood feud get into news chronicles. We can recall a few resonant stories related to this custom; for example, in November 2016, after a major road accident near Grozny, all the relatives of the perpetrator Alam Khadjaev (who also perished in the accident) left the village of Achkhoi-Martan for fear of blood feud. After that, in early December 2016, the SAM of Chechnya recommended its Imams not to take part in funeral of perpetrators of the road accidents, if the latter were in the state of alcoholic intoxication, and not deal with reconciliation of blood feudists in such cases. According to residents of Chechnya, such a decision of the Muftiate may trigger an increase in the number of blood feud cases.

Several stories about blood feud, told by participants and eyewitnesses of events, are given in the article "Payment for blood":

"My father had two wives. He left my mother when I was ten, went to Kalmykia and married another woman there. I never saw my father again, but I heard he had several children from his second wife. My father died a long time ago, just like my mother. Meanwhile, in September 2000, I was visited by several people who came to me at a night. They called me to go out and asked: 'Are you Abdurakhman, a son of a man from a particular place? And they mentioned my father's name.' I answered: 'Yes, I am.' They told me: 'We have come here to announce that there is blood on you. In Kalmykia, your younger brother killed a person from a clan and we declare blood feud.'"

In May 2014, when volunteers from Chechnya, members of the so-called "Wild Division", took part in military operations in the east of Ukraine, one of them told the Financial Times: "We will take a hundred of their [Ukrainians] lives for a life of any of our brothers. Our people believe in blood feud." In connection with that statement, the "Caucasian Knot" interviewed experts who explained that relatives of the people killed in Ukraine did not have the right to blood feud, since that contradicted the adat, and if one of the participants to the conflict professed another religion then no blood feud could be declared.

In the course of the investigation into the assassination of Colonel Yuri Budanov shot in Moscow in June 2011, one of the versions suggested that Yuri Budanov could be avenged for the murder of Elsa Kungaeva, a Chechen young woman, whom the Colonel himself considered guilty of the deaths of his subordinates killed during the second Chechen war 28. In August 2011, Yusup Temerkhanov, a native of Chechnya, was arrested in Moscow, and in April 2013, he was found guilty of the Yuri Budanov's murder. However, in May 2013, the court re-classified the charge against Yusup Temerkhanov from Part 2 of Article 105 (murder motivated by blood feud) to Part 1 of Article 105 (murder) of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation and found the defendant guilty.

In April 2011, in Chechnya, Magomed Taysumov (Tyson), the former deputy commander of the "Vostok", a special battalion of the Chief Intelligence Agency (known as GRU), and a member of the Ramzan Kadyrov's clan, fell victim to blood feud. Investigators then considered several versions of the murder. Meanwhile, all of them were somehow associated with revenge for the Tyson's participation in combat actions during the second war in Chechnya or his crimes against civilians, including kidnappings, murders and extortion 29.

On August 4, 2010, Ibragim Yevloev was killed in Ingushetia, neighbouring on Chechnya. He was the former deputy chief of the state security centre at the Ingush Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) and had earlier criminal record for negligent homicide of Magomed Yevloev, an owner of the opposition website "Ingushetia.ru". Investigators suggested the Ibragim Yevloev's murder could also be connected with blood feud.

Besides, in his interview to the "Caucasian Knot", Ingush leader Yunus-Bek Evkurov mentioned he was aware of cases of blood feud against relatives of members of the armed underground. Like in Chechnya, "reconciliation commissions" are active to resolve conflicts in Ingushetia.

Endnotes

- Blood feud. Big Law Dictionary, by red. Sukharev A.Ya., Krutskih M., 2003; Grathoff S. Fehde // Institut für Geschichtliche Landeskunde an der Universität Mainz.

- Latest assassination attempt on Kadyrov… // Novaya Gazeta, 30.01.2017

- Isa Yamadaev put on the federal wanted list on suspicion of an assassination attempt on Kadyrov // Rosbalt, 01.04.2017

- 'Decided to kill Kadyrov acting out of the feeling of blood feud' // Rosbalt, 01.04.2017

- 'Many people tell me that Ramzan had done it' // Kommersant, 29.09.2008

- Morale-sapping factor of Chechnya // Deutsche Welle, 10.01.2017.

- Tarkhanova Zh. Blood feud, tortures and a lot of uncertainties // Echo of Caucasus – Radio Liberty, 24.01.2017; According to blood feud laws. Why European champion is suspected of double murder // Life.ru, 24.01.2017.

- Albogachieva M.S., Babich I.L. Blood feud in modern Ingushetia // Etnographicheskoye obozrenie, 2010, №6

- Albogachieva M.S., Babich I.L. Blood feud in modern Ingushetia // Etnographicheskoye obozrenie, 2010, №6

- Gimbatova M.B. Blood feud practice of Turkic-speaking peoples of Dagestan in 19th – early 20th century // Lavrovsky sbornik, 2012-2013: Ethnology, history, archeology, culturology / Edited by Karpov Yu.Yu., Rezvan M.E. Sankt Petersburg, 2013, pp.341-343.

- Kaloev B.A. Ossetian-Vainakh ethnocultural ties // Caucasian ethnographic digest. Issue 9, Moscow, 1989, p. 144

- Luguev S.A., Gimbatova M.B. Traditional practice of feudists reconciliation of Turkic-speaking peoples of Dagestan (19th-beginning of 20th centuries) // Newsletter of Institute of Atomic Energy, №4, 2012, p.67.

- Musaeva A.G. Blood feud practice in Dagestan // Contemporary issues of science and education, №1, 2015.

- Luguev S.A. On blood feud among Laks in second half of 19th – early 20th century // Daily household routine of Dagestani peoples in 19th – 20th centuries. Makhachkala, 1980. Pp. 89-107.

- Historical and cultural traditions of Northern Caucasus peoples // Edited by Tishkov V.A., Moscow, 2013, p.80

- Blood feud // Kommersant, 18.08.2003

- Historical and cultural traditions of Northern Caucasus peoples // Edited by Tishkov V.A., Moscow, 2013, p.81

- Historical and cultural traditions of Northern Caucasus peoples // Edited by Tishkov V.A., Moscow, 2013, p.82

- Musaeva A.G. Blood feud practice in Dagestan // Contemporary issues of science and education, №1, 2015.

- Musaeva A.G. Blood feud practice in Dagestan // Contemporary issues of science and education, №1, 2015.

- Historical and cultural traditions of Northern Caucasus peoples // Edited by Tishkov V.A., Moscow, 2013, p.82

- Blood feud in Chechnya: tough legacy of the Middle Ages // RBC, 10.06.2011

- Kokh A. How I understand Chechens. Four opinions / Polit.ru, 03.09.2005

- Basnukaeva M. Chechen system of common law norms // Caucasian traditions of settling conflicts and methods of civil society institutions. Sukhum, 2002, pp. 73, 75.

- New head of Russia's General Prosecutor's Office headquarters appointed in Southern Federal District // DON TR, 14.09.2007

- Ramzan Kadyrov heads Commission for National Reconciliation in Chechnya // Leadership of Chechen Republic 17.09.2010.

- Everything in accordance with feud in Chechnya // Moskovsky Komsomolets, 14.10.2010.

- Blood feud in Chechnya: tough legacy of the Middle Ages // RBC, 10.06.2011

- Blood feud // Kommersant, 02.04.2011

![Tumso Abdurakhmanov. Screenshot from video posted by Abu-Saddam Shishani [LIVE] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mIR3s7AB0Uw Tumso Abdurakhmanov. Screenshot from video posted by Abu-Saddam Shishani [LIVE] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mIR3s7AB0Uw](/system/uploads/article_image/image/0001/18460/main_image_Tumso.jpg)